Last week, the House passed a bill that would prevent the federal government from prosecuting Guantanamo detainees in civilian courts (by cutting off the funds to do so). The Senate is now considering it as part of the 1,900-page omnibus spending bill. This is largely seen as a reaction to the acquittal of Ahmed Ghaliani — the first Guantanamo detainee to be tried in civilian court — of more than 280 charges stemming from the bombings of U.S. embassies in Africa.

The Obama administration is fighting against it, with AG Holder writing a (fairly lame, in our eyes) letter insisting that we absolutely must use civilian courts to deal with terrorists and captured combatants. Essentially, his argument is that civilian courts are a tool that has worked before, so why deny that tool to the executive branch and make it fight the bad guys with one hand tied behind its back?

Ignore the ham-handed attempt to co-opt a common complaint about the left’s frequent insistence on soldiers doing actual fighting with one hand tied behind their backs, lest they rile someone’s sensibilities. It’s a dumb argument. Guantanamo detainees didn’t commit crimes within the territorial jurisdiction of the United States. Their acts are acts of war, or of transnational combat that is more like war than anything else.

Congress is gearing up to do the right thing, but for the wrong reason. The principle should not be “we can’t do this because we might lose in court” — that’s not even a principle. It’s just a weakling’s worry. The principle should be “we can’t do this because it’s wrong.”

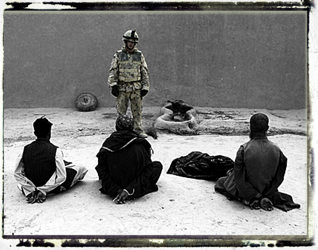

First off, soldiers are not cops. Secret squirrels are not cops. Their job is not to obtain constitutionally admissible evidence in order to secure a conviction in court some day. Their job is to achieve a military end — secure some territory, disable the enemy’s troops, deny the enemy’s objectives, etc. Let’s say a soldier just captured a guy who was shooting at him 30 seconds ago, and wants to find out where the prisoner’s buddies are and what they’re going to be up to next. The Obama folks would require that soldier to treat that prisoner with all the rights due under ever-evolving Fourth and Fifth Amendment law — with the dire consequence that if he fails to do it perfectly, this guy is going to be released by a court, to fight another day.

Who’s asking whom to fight with one hand tied behind their back, again?

-=-=-=-=-

The threshold issue, of course, is whether an enemy fighter taken on the field of combat has the same constitutional rights as an American citizen arrested for a crime. The Holder approach would extend U.S. constitutional rights to everyone in the world. By extending U.S. criminal jurisdiction so far, the associated rights and rules are extended as well. This can be a problem.

Look at Miranda, for example.

First of all, the basic principle that underlies the Fifth Amendment protection here is that Americans don’t want the government to be able to override the individual’s free will, so that the individual convicts himself out of his own mouth. It’s that whole Star Chamber thing. It’s fine if you admit to something on your own, but it’s not okay if you didn’t want to say it, and the government forced you to say it anyway.

The government has awesome powers, so if the government has taken you into custody and you’re not free to leave, that’s a pretty intimidating circumstance right there. If they try to make you talk while in custody, then that’s presumptively an attempt to override your free will.

So to ensure that anything you say is really voluntary, and not being forced out of you, the government has to make sure you understand that you don’t have to say anything, and that if you do say something they’re going to use it to try to convict you. Once you understand that, and agree to talk anyway, you’re now presumptively acting voluntarily, and our Star Chamber concern goes away.

Now, the government is free to ask questions all they want without mirandizing you first. They just can’t use your statements against you if they do that. So they can ask questions without the Miranda warnings if they’re just going to get intelligence on other people’s crimes, and they don’t care if what you say is going to be admissible at your trial.

The problem is, how is anything this prisoner says not something you’d want to use at his trial? Any useful intel is going to be proof that he knew it, that he was involved. Miranda is always going to apply.

And if the 19-year-old soldier who captured him didn’t know his con law as well as the Supreme Court, he could well get it wrong. And the guy could go free to wreak havoc another day. As if he happens to be roaring his questions down the barrel of a rifle.

And most military and intelligence interrogation is specifically designed to override one’s free will. That’s the whole point. Your captive does not want to talk, for reasons of honor, loyalty, patriotism, the safety of his buddies, etc. He’s probably been trained to resist interrogation. This is not like a criminal suspect who admits his wrongdoing because he feels guilty, or to get it off his chest, or to do the right thing, or to get a lighter sentence. Criminal suspects and military/intel detainees are two entirely different animals. It is imperative that detainee interrogators do precisely what the Fifth Amendment doesn’t want police doing.

Well, hang on, we hear you saying. What about the public-safety exception? Aren’t police allowed to question without Miranda to get info so they can prevent a threat? Wouldn’t that fit trying to get intel on what the terrorists or enemy troops are plotting?

No, it wouldn’t. The public-safety exception only works if the questioning is absolutely necessary — there are no other reasonable options — to prevent an immediate threat to public safety. Terrorist and combatant plans aren’t really immediate. “Where did you plant that roadside bomb” might count, but “what are you guys planning to do next” doesn’t.

Also, if you extend the public-safety exception to cover these kinds of things, then you’ve pretty much swallowed the entire rule. Because once you’ve gone beyond the necessity of an immediate present danger, pretty much any criminal case is going to fit the mold, and the Fifth Amendment goes out the window.

Well, you say, isn’t there an argument that Miranda doesn’t really apply to military or intelligence interrogations? No, not a good one. It hasn’t been litigated, so there’s no law on it, but whenever we extend the power to prosecute, we also extend the constitutional protections that go with it. Failure to do so would undermine the very protections we hold most dear.

And none of this has really been litigated. The law is nonexistent, or unclear at best. Should soldiers and CIA operatives really have to be thinking about all this when they should be fighting a war. We already have young JAG officers looking over the shoulder of commanders back at the base. Should we have them out in the field okaying everything the soldiers would do before they can do it? Soldiers aren’t cops.

It’s backwards to argue that civilian criminal prosecution must remain an option. These are not civilian matters. These are not crimes. It’s not a mistake to preclude the feds from using this tool, because it’s not the right tool. And make no mistake, the administration doesn’t merely want to keep the option open — they want this to be the only option. Keeping with the tool analogy, they’re saying we should keep open the option of using a saw to drive a nail, when doing so would be not only wrong but dangerous.

1 Response

[…] this blog. For good reason — he’s been something of an idiot on profiling, miranda, terrorism, etc.. But today he did something praiseworthy, and we’d be out of line if we didn’t […]